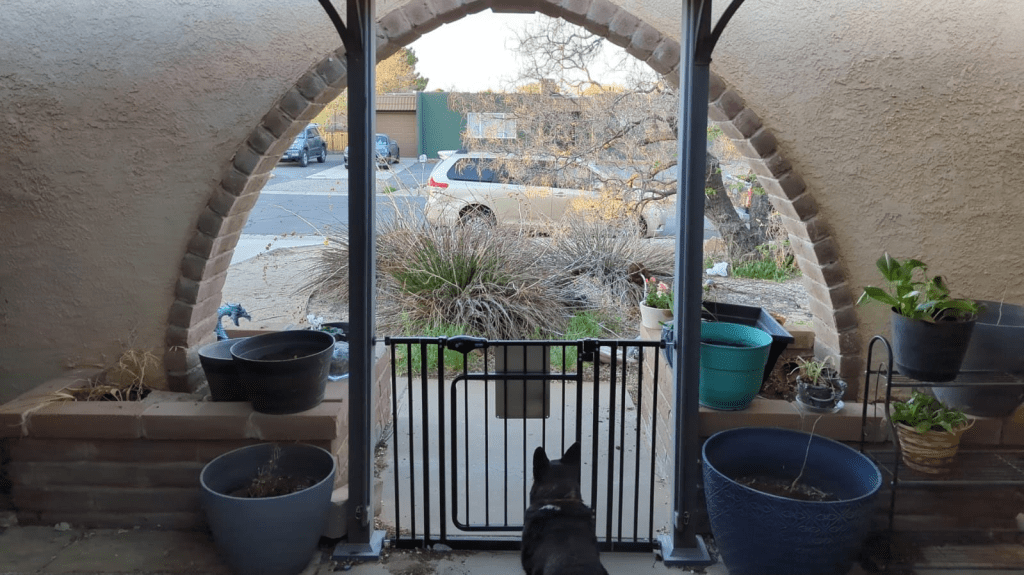

More years ago than I really care to put a number to, the mister and I bought a house with a courtyard.

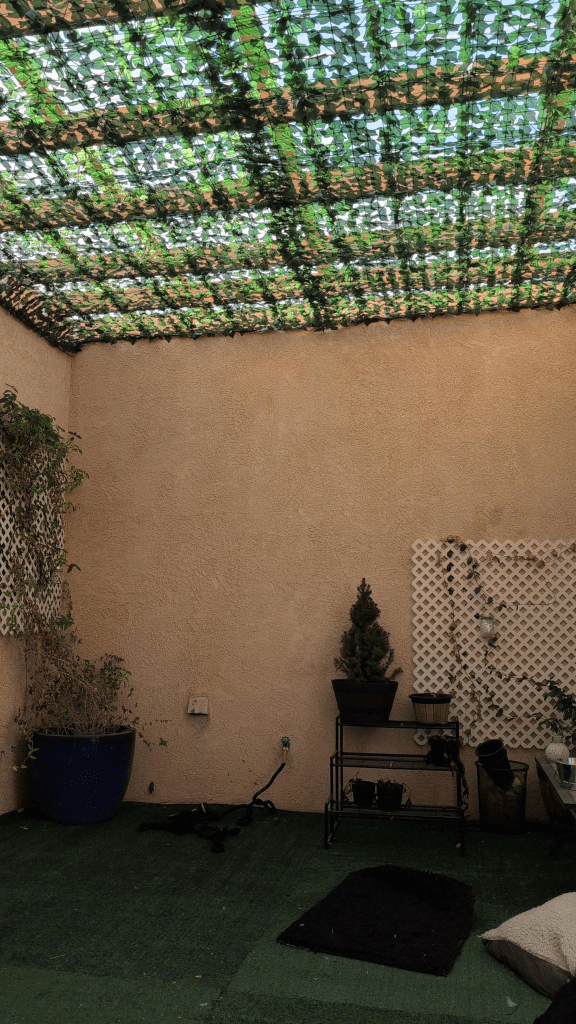

Without trying to sound deprived, I’d never had a place with a courtyard before, and I was charmed by the idea of it while be daunted at what the heck to DO with it. We put up various sunshades over the years, installed a container garden, and eventually put a roof on the whole darn area.

But it still wasn’t quite right. I came back to the bareness of the sand colored stucco walls over and over again making the space feel colorless and barren… and then I had an idea.

We put faux grass down instead of carpet, and faux leaves on the ceiling to give a nice, leaf dappled light effect.. and that was good. Wouldn’t it be interesting, I asked the mister, if we had tree trunks painted on the walls to have a foresty/glade kind of a feel?

We agreed it was an interesting idea, and let it simmer for a bit. To be fair, there’s been a large number of small projects we’ve been working on since covid kept us more in our house than out of it. But as spring started to roll around this year, I started getting more serious about putting the finishing touches on the courtyard.

Reddit to the rescue! I posted in my local subreddit to see if anyone knew of anyone that would be tempted by such a project. That guided me to two different muralists that both offered free quotes.. so I figured what the hell and set up two meetings for a Saturday.

This is where stuff got wild.

First we met with Don from Things on a Wall.. and, not to spoil anything, but you did read the title of the post, right? We walked around the space and talked about what I was looking for. We chatted for about an hour, and he said he’d come back with a proposal in a couple of days. Fair enough.

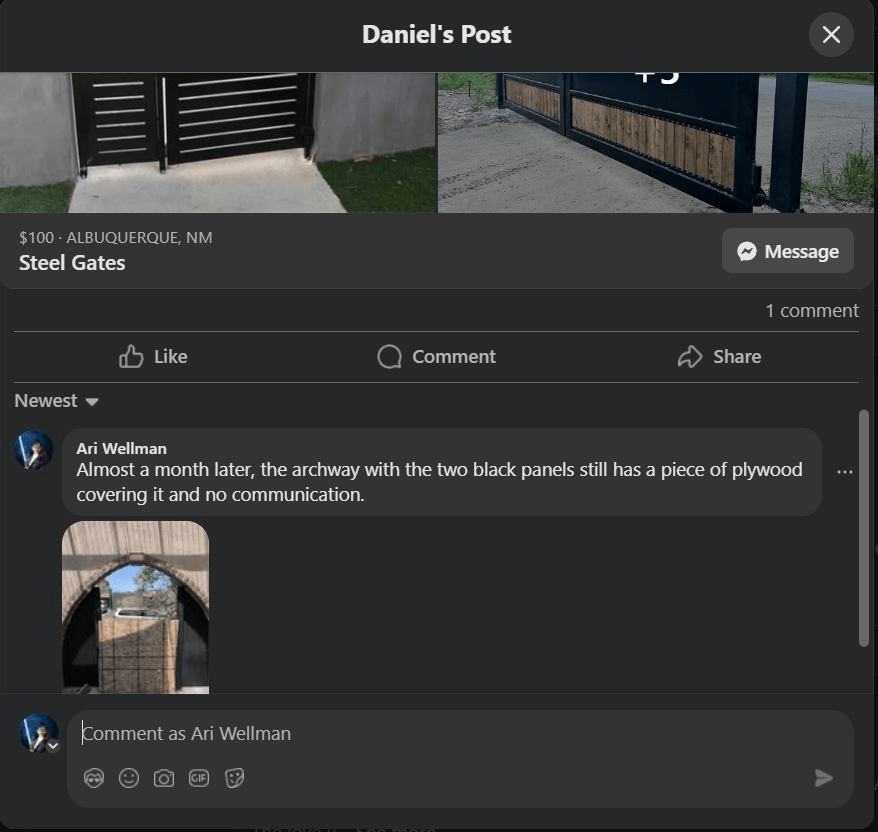

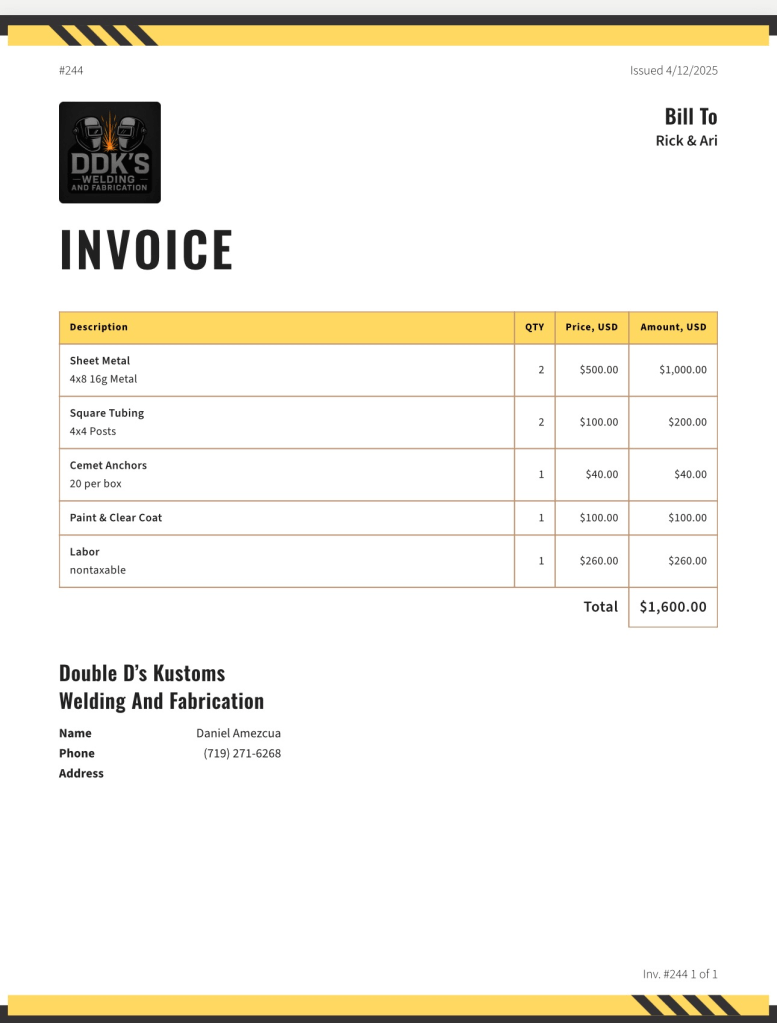

Next we met with muralist #2. They seemingly forgot what day we’d set the appointment for, showed up late, and frankly spent more time pumping me for networking information than talking about the project itself. They took measurements and informed me what the base cost would be, but that there probably wouldn’t be full paint coverage in the proposal anyway. I kind of shrugged and said if it was what I was looking for, I expected to pay a price for that and that was that. They promised the proposal same day and I was the one that suggested they may want to take a little time with it. Fairish enough.

The proposals came in… and what was immediately clear was that Don had listened, heard what I was saying, and created something that embodied exactly what I wanted as though he’d seen into my mind. He was able to start within a week, and that was more than good enough for me.

The other proposal came in.. and I’m genuinely not trying to be mean, I honestly don’t understand how anyone that was listening could have created such a thing thinking it was something I wanted. And though only about half to two thirds of the wall were to be painted, it had been costed out at the maximum possible price. Which, frankly, would have been reasonable if I was buying a used car, but not so much for this project.

So yeah, we went with Don’s proposal and waited with excitement to see what was next.

Yall, I know what it is to work with folks on home improvements, and I was steeled for it.. and I didn’t have to be. Don was extremely gracious, made friends with 2 out of the 3 pups in minutes, sought feedback regularly, and really made the entire experience fun. Within a week, my walls ran riot with trees of all kinds, from fall to spring to summer and my dream forest came to life.

There’s still a bit of work to go here.. those boxes you see are the sectional couch I ordered for the ‘reading nook’ side of the courtyard.. though you’ll noticed the writing nook is already quite operational.

I can’t tell you how glad I am that we did this- how much more welcoming, unique, and enjoyable the space is. With the weather warming up, I know I’ll be spending a lot more time here, daydreaming in the enchanted forest Don has created for me.

If you’re local to Albuquerque and you like what you’re seeing, check out thingsonthewall.com. I cannot recommend Don highly enough as both a professional and a person, and heaven knows we all have a bunch of blank walls to stare at. And if you’re thinking your stucco is too rough for this kind of thing.. I’m going to ask you to zoom in closer on the first, unpainted picture… I honestly expected to be told that I was going to be spending some time on a sander to prep the space… that didn’t happen, and I could not be more pleased with the results.

However, I also feel I would be remiss if I didn’t give a brief warning.. this is addictive. I’m already looking at other blank walls and thinking about what Don may be able to do next!